Abstract

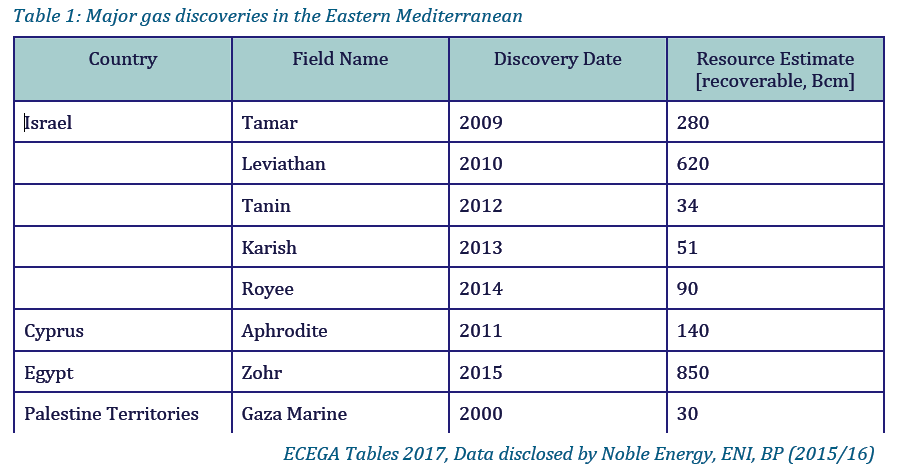

In recent years significant natural gas reserves have been discovered in the Eastern Mediterranean basin. Israel marked the beginning of a regional gas rush with the discovery of Tamar in 2009. In 2010, the country announced the much larger Leviathan field, followed closely by the Cypriot Aphrodite in 2011. The vast Zohr field off the Egyptian coast was announced by Eni in 2015. In a region torn by political fractiousness, historic instability and burgeoning energy demand, the discovery of these reserves has been met with rampant optimism for the regional gas outlook, and for the achievement of political and economic stability. Not so far away, the reserves have been quickly vetted as crucial for the EU’s long-held energy diversification goals and an important new source of revenue for oil and gas majors.

Can the promise of Eastern Mediterranean gas help the region overcome historic tensions and sensitivities? Will Europe alleviate its energy dependency woes and secure new supplies and new routes to motor its gas-hungry power system? How easy energy majors will redirect crucial investments to exploit the reserves? And ultimately, how and to whom the Levant gas will be exported? The answer to these questions will be decided by geopolitics, rather than commodity economics, but the facts attest that six years after the pioneer big discovery, the world is still awaiting its first cubic meter of gas from the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

At the beginning of last year, the European Centre for Energy and Geopolitical Analysis was commissioned to examine the key issues and latest developments in the region with an emphasis on the opportunities and challenges for regional energy cooperation, and the prospects for exploitation of the gas reserves and their impact on the EU energy security question. The analysis meant to particularly evaluate the investment viability for energy majors to contribute resources to exploration activities and infrastructure development. What follows is a short adaptation of this work that will add to the intellectual inquiry in the field.

The East Mediterranean Geopolitical Chessboard

An American Geological Survey estimated in 2010 that the Eastern Mediterranean has more than 3,5 trillion cubic meters (Tcm) of gas reserves and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil1. The hydrocarbon resources found so far amount to 2,1 Tcm and are all located in the Levant Basin which straddles the territorial waters of Cyprus, Israel, the Palestine Territories, Lebanon and Syria. The major fields are remarkably close to each other: Zohr is some 90 km away from Aphrodite, which is 7 km away from the Israeli Leviathan. Lebanon has not yet commenced exploration rounds but preliminary surveys point to considerable gas reserves in the Lebanese shelf as well. The proximity of the gas fields makes joint exploration especially advantageous: the economies of scale will significantly reduce investments requirements and catalyse the emergence of regional energy cooperation. Nevertheless, exploration has proven difficult, and investment flows are not forthcoming.

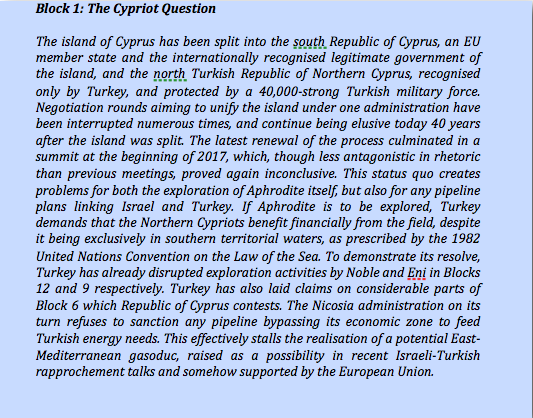

The reasons for this are manifold, and intersect domestic political and legislative dynamics, intra-regional historic rivalries and international macroeconomic uncertainty and commodity price downfall. Maritime borders remain to be agreed between Israel and Lebanon, and crucially between Cyprus and Turkey. Distrust between Israel and the Palestinian Authority has hindered negotiations for the development of the Gaza Marine, founded by British Gas 18 years ago. Turkey and Israel were almost at the edge of a war in 2010, when Israeli security forces killed 10 people on a Turkish ship delivering aid to the Gaza strip; and Egypt interrupted key gas exports to Israel in 2012 without providing a compensation for the breached contract; Syria is ravaged by war; Egypt remains split into opposition groups; and just in 2014, Turkey threatened to blacklist all companies engaging in exploration and drilling activities offshore Cyprus. After intercepting a Norwegian ship sanctioned by the Cypriot government to conduct seismic surveys, no other company has tempered with Erdogan’s resolution. Recent attempts at reconciliation between most notably Israel and Turkey, but also Turkey and Cyprus give some scope for cautious optimism [see below] but clearly too scant to predispose for a joint exploration in the foreseeable future.

The unfavourable political status quo is worsened by domestic legislative dynamics which interfere with the development of any viable energy investment strategy. In Israel, the exploration of the Leviathan has been brought to a standstill by the ongoing political struggle between the Government and the Supreme Court, the initiation of price and export controls and constant changes in energy regulations. In Lebanon, the energy framework makes it impossible for foreign companies to drill in supposedly gas-rich Lebanese waters. In Egypt foreign companies cannot power the domestic electricity system. And in Jordan, the population’s antagonism towards Israel makes importing Israeli gas a thorny domestic subject.

Options for the Monetisation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Reserves: Infrastructure and Customer Base

The complex geopolitical environment in the region in combination with the global downward price cycle has made is challenging for countries to mobilise financing for exploration activities, secure customers for the gas and agree on and/or start building key export infrastructure. There is also no consensus as to where and how the gas reserves should be exported to. Despite much articulated options to export the gas via pipeline to Europe and/or Turkey [examined below], as of today, none of the fields has secured export contracts. This effectively translates in delays in exploration and commercialisation of the resources and failure to monetise the region’s offshore wealth in real terms beyond the laudable and often misleading rhetoric and political statements.

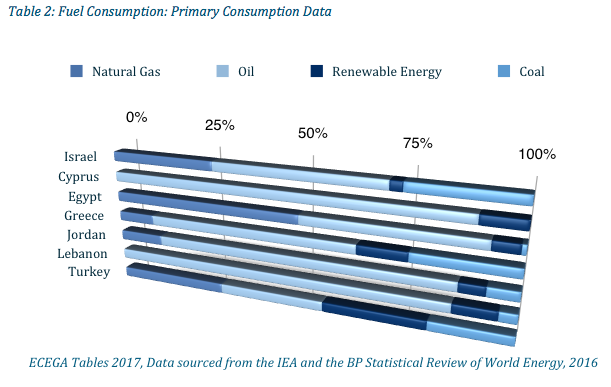

In this context, the most viable option for monetising the gas reserves is domestic utilisation rather than export. None of the concerned states has gas as major part of its energy mix, thus, gasifying the regional economies with own reserves will be cost-efficient and will provide substantial energy security, environmental and budgetary benefits, while helping the region, as well, meet its emission obligations as under the Paris Protocol. Israel has already started converting its oil-fired power stations to gas, and the process is likely to be emulated by its neighbours, given the potential accumulated benefits [see Table 2: Fuel consumption in selected Eastern Mediterranean states].

Regional export scenarios would be a second-best option for the development of local resources, yet one which belies significant challenges [read below].

The export across the Mediterranean into Turkey and Europe is not considered by the author as a viable option on this stage and the political, financial and technical challenges of this alternative would be examined at the end of this paper.

To provide a better grasp of the issues grappling the Eastern Mediterranean states, the paper will examine each of the countries individually. The domestic context varies significantly, and this country-by-country inspection will serve to inform the analysis on the realistic potential for the offshore gas deposits’ monetisation by each of the states individually, and as a potential collective.

Israel

Israel has the second largest reserves in the region, behind Egypt with a proven capacity of 199 Bcm of reserves2. The country relies on foreign expertise and companies (notably the American Noble Energy) for the exploration and production activities necessary to exploit its offshore wealth. Nevertheless, stringent domestic regulatory regime and antitrust investigations pertaining to price and export controls, as well as diplomatic tensions with key potential export markets have somehow created an unwelcoming environment for energy majors. At the centre of the controversy which has embroiled the country for the past one year is the Natural Gas Regulatory Framework. The bill guarantees stable price and no legislative change for a period of 10 years, a notion which has attracted antitrust charges from the country competition authority, and ultimately resulted in the Supreme Court declaring the Bill unconstitutional last March, giving the Government one year to find a legal solution or abandon the framework altogether.

In an important sign of the cracks in investors’ confidence incurred after the prolonged legislative jigsaw, the Leviathan consortium, headed by the Texan Noble Energy, announced in December that without a financing envelope of $10 billion, further exploration activities would be cancelled. Noble Energy, which has sustained global losses of $2.4 billion in 2015, has planned to finance the Leviathan exploration by Tamar bonds - debt issued against revenues from the Tamar gas field which powers the Israeli market at a guaranteed stable price of $5.5 MBtu - but the recent demand of the Israeli Electricity Corporation following the Supreme Court judgement, to equalise power generation costs with a price drop of $1,5 MBtu makes the Noble strategy obsolete. The revoked by the Supreme Court price and export guarantees, compounded by the lack of secured customers and/or routes-to-export makes the investment case for Noble even less certain, and thus, have effectively stalled the Leviathan activities. Wriggling out of this situation is would be a tricky endeavour for Israel. The country has stuck itself in a complex Catch 22 situation - further investment in exploration activities in the Leviathan field would depend on secured export routes and contracts; but, naturally signing long-term purchasing agreements would ultimately depend on stable production and export infrastructure.

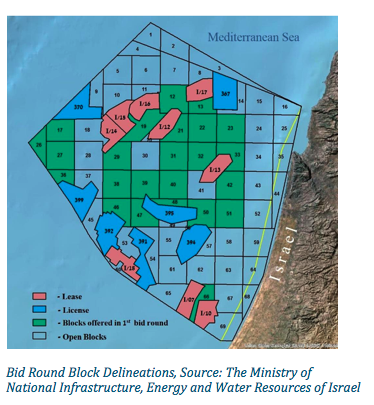

To comply with the ruling, the government compelled the Tamar and Leviathan stakeholders to divest their rights in the Tanin and Karish fields, thus ensuring diversification of the energy ownership3. Last November, the government also invited bids from new companies for gas and oil exploration licenses in 24 blocks [indicated in green in the enclosed map] with the aim to increase the number of energy players in the gas market but also most notably to turn Israel into a “gas empire” as proclaimed by the Minister for National Infrastructure, Energy and Water Resources - Yuval Steinitz. Steinitz’s expectations are recovery of 3 Tcm of natural gas, a capacity validated by a study by Beicip-Franlab, the French consultancy, commissioned by the Israeli Energy Ministry a few years ago. The current tender will close at the end of April, 2017. International Oil Majors, most notably Shell, Total, but also Eni, which discovered Zohr two years ago and is considered to boast the most advanced geological understanding of the region, have shown reluctance to participate in the bid due to the complex geopolitical climate (with ongoing territorial disputes with Lebanon and Palestine) and the still unclear routes-to-market of potential deposits. Further, given the depth of the delineated blocks (up to 1,800 meters), the cost of exploration might further stymie energy companies’ enthusiasm in a global context of austere upstream budgets. As of mid-March, 2017, there is some indication that Exxon Mobile might participate in the bid (implied by Israeli Energy Ministry officials) but no official confirmation from the company has been issued as yet. Exxon is already involved in the exploration of the close Cypriot offshore together with Qatar Petroleum, but the company’s activities there have not garnered any positive results so far.

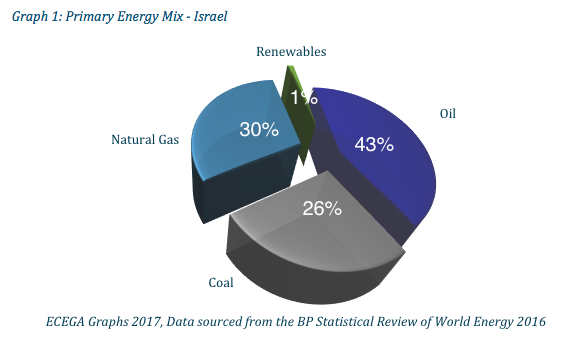

The difficulty in attracting more investor’s interests and industry commitment is also compounded by the lack of solid customer base. To rectify that and potentially reignite the Leviathan exploration, focusing on a domestic diversification of supply seems to be the most pertinent option for Israel. The country has made a pragmatic choice to increase the amount of gas in its energy consumption, and since 2010 has increased gas share of primary fuel needs from about 1/10 to almost 1/3 of fuel consumption and 1/2 of electricity generation [See Graph 1: Primary energy consumption in Israel] today. Expectations are that this figure would go up to 80% by 2020. Last year (Q1, 2016) a small contract (6 Bcmy for 18 years at the cost of $1,3 billion) was signed with the Edeltech group (Israeli-Turkish consortium and the largest private power producer in Israel) but the final investment decisions have not been made yet (Q1, 2017). This agreement was followed by a bigger one with a new privately operated power plant in May, 2016 at the cost of $3 billion for 13 Bcm capacity. These are positive steps. The Israeli hydrocarbon deposits would also be crucial in the development of desalination plants, to provide water to the domestic market but also potentially to solve the region’s chronic water shortages. The country would be well-advised to invest further in using its offshore gas wealth to amplify its regional water leadership status.

While easier to monetise than nebulous export contracts, the focus on domestic use belies its own challenges. The focal one is the insufficient domestic gas pipeline network. Currently, Tamar which supplies 60% of the gas consumption in Israel is connected by only one pipeline to the shore, with only one gas treatment facility and one onshore reception centre. This represents an urgent security challenge for Israel and the country should both try to diversify its domestic gas supplies from different fields but also diversify the infrastructure network to avoid a complete black-out in case of technical malfunction and/or any other type of blockage on the current pipeline.

Looking outside of its immediate borders, a web of pipelines connecting Israel to its neighbours would be technically and financially viable option which would unlock the Leviathan predicament. The Palestinian Authority, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria are all potential markets. However, the geopolitical sensitivity trumps commercial sense. Most of its neighbours question the legitimacy of the state of Israel. Public opinion in Jordan and Lebanon is strongly against using Israeli gas, while Syria is ravaged by war. Also, following the above mentioned regulatory turbulence in Israel, Jordan’s National Electric Corporation dropped-out of American mediated talks for Leviathan gas imports. Shell and Union Fenosa, which have expressed some interest in the Leviathan reserves never proceeded to a contract signing ceremony as well. An agreement for a 20-year supply of gas from Leviathan to the West Bank, signed 3 years ago (2014), despite being technical and commercially sound, and having a potential game-changing result in reducing the escalating energy famine in the enclave, have not produced any tangible result as well - the escalating feud between the state of Israel and the Palestinian Authority in recent months and the official authorisation of yet more Jewish settlements in March, 2017 is not likely to bolster the energy export project either.

The country has tried to achieve some strides in its relationship with Egypt. The existing Arish-Ashkelon pipeline between the two countries would potentially permit a quick production to market of the Leviathan resources and assuage investors. In 2015, the Israeli government reached a deal with the Egyptian privately owned Dolphinus group for the export of 5 Bcmy for 7 years from Tamar and an additional 4 Bcmy for 15 years from Leviathan using the Arish-Ashkelon link. The agreement was legally challenged in Egypt due to Dolphinus registration in the British Virgin Islands which according to domestic regulation prohibits it to deliver gas to the Egyptian domestic market4. Solution to the legal challenge has dragged through the bureaucratic system for over 2 years and might never leave the court rooms. The problem has been compounded by Egypt’s newly found energy prowess which makes Israeli gas less a necessity for Egypt. The bumpy history between the two nations and the susceptibility of the pipeline to terrorist attacks has somehow influenced investors’ interest as well5.

Israel has also tried to explore LNG options as a potential export vehicle for its gas reserves. Egypt’s Damietta LNG plant operated by the Italian ENI and the Spanish Gas Natural has already been targeted for the export of 70 Bcm of gas from Tamar; Idku in northern Egypt, operated by British gas has been evaluated as an option for the Leviathan field. But the open and very visible efforts to reach an agreement belie lack of tangible success so far. The coming onstream of cheap Australian and US LNG would further derail market prospects for any Leviathan LNG, even if Egypt grants its accord for the use of its LNG plants.

A lucrative market in the proximity of Israel’s deposits is Jordan - a country with frail energy security and bursting energy demand, partly fueled by the unprecedented number of refugees the country has harboured, currently the highest per capita rate in the world. The country imports LNG gas via a floating storage and regasification unit - an expensive and not very stable option. A sound agreement was reached between Noble Energy and Jordan’s National Power Electric for 8,5 Mcm/day over 15 years for the cost of $15 billion which despite its financial advantage over the LNG imports, was vetoed by the Jordanian public in a strong sign of civic resistance. Another industry deal, with the Arab Potash and the Jordan Bromine Chemical Companies for 2 Bcm of Tamar gas over 15 years might garner less public opposition due to its industrial character but also isolation from the kingdom’s center. Nevertheless, since the deal signing ceremony back in 2014, no shipments have been made as yet.

While sizable, the potential of the Israel’s hydrocarbon deposits has not been harnessed at present. and the prospects for the immediate future do not provide a ground for optimism. The routes to market are complex, and geopolitics makes investment flows hard to secure. This being said, and despite the identified challenges in exporting gas to its neighbours, Israel might still achieve better deals with neighbours by intensifying its regional diplomacy than relying on trans-Mediterranean pipelines and out-of-region export options [read below] which are at present mere pipe-dreams fueling populist rhetoric rather than a realisable and economically sensible projects. Despite the signed on 3 April, 2017 preliminary agreement with Cyprus, Greece and Italy to export Israeli gas to Europe, the author of this report is sceptic on the viability of this project, both in terms of technical and financial feasibility [read below] but also regarding investment flows and industry involvement amidst low gas prices and political instability. The East-Med pipeline is a bold gambit on both Israeli and European side which would not foster the desired outcomes and the reasons for this will be examined at large at the end of the paper.

Cyprus

After the Leviathan find in Israel, exploration of the Cypriot offshore was prompted with high hopes both by the island administration but also at European level. Noble Energy was charged with the exploration and in 2011 the company announced a hydrocarbon deposit with an initial estimates of 230 Bcm of reserves. Aphrodite as it was called promised to start exporting by 2019. A bold plan for the development of a sophisticated LNG plant in Vasilikos was quickly blueprinted and hopes for the island nation to become a regional gas hub able to liquify and export gas coming also from Leviathan were fueled by domestic pundits and European officials. Profitable contracts with European and Egyptian markets were anticipated and the discovery was set to become a game changer both for the island sluggish economy but also for the EU diversification goals.

This was in 2011, and as it often happens when an issue is surrounded by much hype, time manages to dissipate the sand castles and leave a deformed pile of sand and broken shell pieces. Since 2011, the initial estimates have been downgraded several times, and exploration rounds in Blocks 6, 8, and 10 (third since the discovery of Aphrodite) by Total, Eni/Kogas, Exxon Mobil and Qatar Petroleum all concluded last year [2016] have not ascertained the same levels as in the neighboring Zohr. Today, the revised deposit estimate stands at less than 140 Bcm, or just enough to gasify the island’s entire economy for about 2 decades. The limited reserves imposed a reconsideration of exploration tactics but also export options. While some further exploration rounds are planned for Blocks 10 (Exxon and Qatar) and 11 (Eni and Total) for 2017 and 2018, the grand visions from 2011 were quickly abandoned and the ambitions seamlessly tempered.

The limited size of Aphrodite hydrocarbons makes them bankable only if developed in synergy with the Leviathan field, but the two nations have continuously failed to agree on a unitisation agreement, despite an intense series of tripartites between Cyprus, Israel and Greece for the past 4 years all attesting to the need of such agreement. In the absence of cooperation between Israel and Cyprus, the $6 billion worth LNG plant in Vasilikos will lose its appeal to potential investors since 140 Bcm can hardly justify the solid financial envelope necessary. The much publicised agreement of 3d of April in the presence of EU Energy chief Canete does not show any sighs of leading to a unitisation contract either6.

As in the Israeli context to an extent, the sole possibility for Cyprus to quickly and cost-efficiently develop Aphrodite would be existent Egyptian LNG facilities (Idku and Damietta). But there as well, no agreement has been reached between Cyprus and Egypt. The issue might be compounded by the recent Zohr discoveries which both negate Egypt’s need for Cypriot gas but also puts Egypt in a stronger position in negotiations and contracts.

The option of Cyprus becoming a key point along the East Mediterranean Pipeline (read below) has been flagged several times but this project as this paper will examine remains far-fetched. The issue is further compounded by the ongoing territorial dispute between Cyprus and Turkey [read in block 1] which is unlikely to be resolved soon.

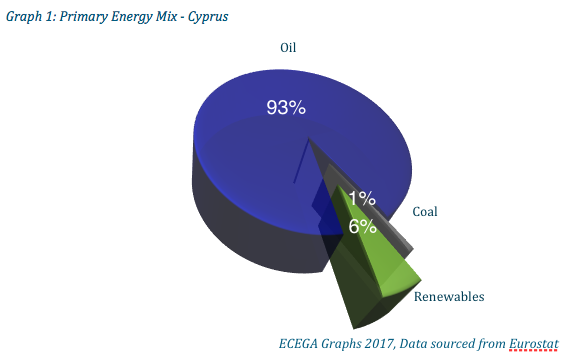

Without a bonfire of export options, the logic would predispose a focus on domestic utilisation. Nevertheless, the Cypriot administration has not been proactive in assessing the viability of moving away from oil and gasifying at least its power sector. The heavy dependence on oil belies considerable risk, not only in terms of finance and dependence on exports, but also related to carbon emissions [Graph 2: Eurostat data on Cyprus primary energy mix]. This anguished state of adjusted ambitions, lack of clear timeframe for exploration and unearthing of the reserves, and no final investment decision on Aphrodite, 6 years after its finding(!) makes it fiendishly hard for the Cypriot government bur also for industry and policy officials to defend the idea of Cyprus as a game changer in the regional gas markets. The rhetoric has clearly changed and in the fourth Eastern Mediterranean Gas Conference in Nicosia last week (14-15 March, 2017), the accent on regional energy cooperation while reiterated, as expected, with the typical absence of production, infrastructure and monetisation strategies and data, the focus on Cyprus was less grandiloquent than in previous such gatherings. In some sign of hope for the island’s administration, Luca Bertelli, CEO of Eni Spa announced that the company believes a bigger field (comparable to Zohr) is probable in the Cypriot EEZ but not further information or seismic surveys data has been presented. Also, Total has recently acquired 50% of the ENI participating stake in Block 11, which must be based on some seismic data to justify the investment and/or rather ENI has been willing to diversify its bold gambit in the region. Whatever the reality behind Total’s involvement, in the absence of a miraculous new find off the Cypriot coast and a similarly miraculous reconciliation with Turkey and an agreement on exploitation of the found resources, Cyprus energy future is bound to depend on either domestic gasification or a solid agreement with Israel.

In terms of energy cooperation, last November, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to strengthen energy cooperation between their countries. What that will mean in practice remains unclear. A pipeline from Cyprus to Greece would be expensive and technically challenging because of the structure of the seabed between the two countries. Geopolitical tensions between Cyprus and Turkey make a pipeline between those two countries unlikely. Exporting Israeli gas to Cyprus for re-export has been mooted on several occasions, but little material progress has been made so far. On April 3d, 2017, a preliminary deal without much substance was signed in a ceremony in Tel Aviv in the presence of amongst others EU’s Energy and Climate Commissioner Miguel Arias Canete but beyond the publicity, the agreement mainly consists in agreeing to meet again to discuss the behemoth East-Med pipeline - a much vetted project surrounded by pompous rhetoric and regular pontifical summits to promote it, but without any tangible practical feasibility attached to it.

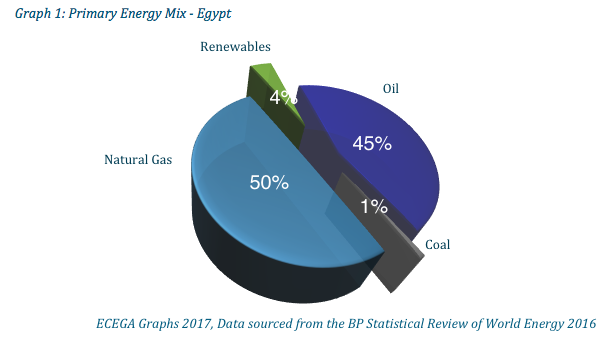

Egypt

In August, 2015, Eni Spa made an announcement which startled the world - a discovery of a 850 Bcm - strong gas deposit was made in offshore Egypt. The value of the find was estimated to stand at the staggering $100 billion. The discovery of Zohr in 2015 generated important geopolitical ripples across the region. Almost overnight, the massive field abrogated previous export scenarios developed by both Cyprus and Israel - from a potential needy importer, Egypt turned into an almighty geopolitical power, which would ultimately decide the fate of the region in terms of energy potential and political cooperation and stability. This is due to both the vastness of the reserves, but also, primordially to the operational export infrastructure in place and the anticipated quick production-to-market process.

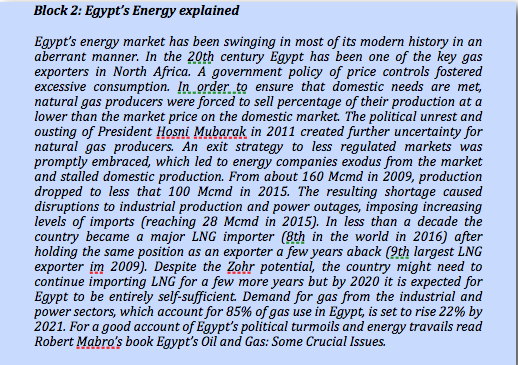

Domestically, the benefits of the Zohr find are colossal. Egypt relies exclusively on gas for its primary energy consumption, and the subsidised domestic pricing for energy has led to a staggering budgetary deficit and external debt exceeding $3 billion - a situation much intensified by the reduced tourism and Suez transit fees receipts, and with potentially explosive outcome in an already unstable country7.

Despite being the last to join the gas race, Egypt can be considered as the most mature in terms of exploration plans and prospects. The country has an established gas infrastructure, including subsea operations and two LNG terminals - Idku and Damietta which can liquify up to 20 Bcmy. The country has also a lease until 2020 of floating storage and regasification platforms FSRR originally intended to accommodate imports, but currently idle. While Egypt will certainly try to export some of the Zohr gas, it will ultimately serve more to satisfy the growing internal demand and alleviate the financial burden and huge debt the country accumulated over energy imports [Graph 3: Primary Energy Consumption - Egypt]. Thus, this author does not believe that Egypt will demonstrate a vivid interest in pipeline projects linking Zohr to Europe and/or Turkey and will utilise the gas to fuel and solidify its economy and potentially to spur some long-awaited domestic stability. The country has smartly embarked on structural reforms making the investment climate especially advantageous for foreign direct investment. In a strong sign of confidence, BP acquired in 2016 10% interest into the Shorouk concession containing ENI’s Zohr mega-field for $375 million. In addition, the company operates the Atoll (40 Bcm) in the North Damietta Offshore Concession in the East Nile Delta, and the major West Nile Delta project (142 Bcm), both expected to start production in the next two years. Shell also has a stake in the Egyptian offshore market. Nevertheless, the relationship is marred by inherited confrontations - after the takeover of BG, Shell and the Egyptian government still need to decide on whether the Egyptian General Petroleum Company will repay Shell the $1 billion owned to BG or will agree to higher gas prices $7 MBtu instead of the current $5,8MBtu. Agreement between the two parties remains to be found, in the meantime Shell exploration of the 9B concession area is stalled.

The country also opened in 2016 an international tender for 11 new offshore oil and gas blocks in the Mediterranean and the Nile Delta, with preliminary estimates showing to an additional 21 Mcmd capacity.

Lebanon

The internal government divisions in Lebanon combined with volatile security and business environment has been an effective deterrent to any attention to the country’s energy resources. The country is today entirely dependent on oil imports with almost no consumption of natural gas. Nevertheless, recent estimates point to 420 Bcm of recoverable offshore gas deposits and more than 850 million barrels of oil. As of today, no company has been granted exploration rights (despite 46 approved applications from world energy majors as far back as 2013), neither the regulatory regime for exploration discussed at government level. Progress is not expected soon due to internal political gridlock - the country has been effectively functioning without a budget for the last 12 years, with unstable government and fragmented political spectrum and allegiances (Lebanon had 25 elections since 2014); the imploding refugee crisis in the country further erodes stability - Lebanon has admitted more than 1 million Syrian refugees and attributed considerable resources to handling this crisis. Until the political stalemate in the country is bypassed, the exploration of the Lebanese offshore will not be a priority and exploration rights will not be granted, despite some renewed activity in the past few weeks on this front8. In addition, the Lebanese reserves are located in between two geological basins, which makes potential exploration particularly challenging (and costly).

In terms of utilisation potential, gasifying the Lebanese economy will certainly make use of its offshore wealth. Currently the country uses exclusively oil (94% of primary consumption) with some limited renewables (about 4%) and coal (2%). With a population of about 7 million (including the 1 million Syrian refugees), the majority of the gas finds though would be destined for exports and this might be in a direct competition to the Leviathan gas. And the lack of infrastructure or LNG facilities would halt investment prospects. Again, the LNG plants in Egypt might prove vital for the exploration prospects of Lebanon as well. But this would be an issue of the future.

The maritime boundaries dispute with Israel is also inhibiting progress. The two countries contest the 1949 armistice line agreement and an area of about 850 square kilometers. While force has not been used, the rhetoric has escalated at times, creating an inhospitable commercial environment for energy companies. Just last month (March, 2017), the Israeli government announced plans to develop a maritime areas law, clearly establishing Israeli sovereignty over the disputed territory, a step which was qualified as ‘expansionist plot’ by the Lebanese parliament saying that ‘a spark of war is looming on the horizon’. More recently, and as a response to the Israeli law announcement, Lebanon included contested territory in its licensing tenders, thus further complicating the relationship with Israel.

Europe: the incessant odyssey of thirst and diversification

One trait has been a constant feature of the European project throughout the many years of evolution, attempted solidification and aspired Europeanisation: the continent has always been energy hungry and energy poor. And this hallmark of the European Union has influenced the block’s external relations but also internal (intra-Member state) ramblings, Council vote group formation and nexus of opaque allegiances, direct and implicit, with domestic or third country energy companies. And while dependence on one supplier has been chastised openly, scenarios to diversify away of this exclusive dependence have often been developed hastily without a proper structural, economic or geopolitical landscape evaluation - as a drowning men holds to a straw to tempt remaining on the water’s surface, the EU has used any vaguely possible scenario to blueprint grandiose plans for energy abundance and affordability. The outcome is always bound to be underwhelming.

True to purpose, in terms of the Eastern Mediterranean gas, the EU was amongst the first entities to loudly applaud the potential. The 2015 EU Energy Security Strategy clearly reiterated the importance for Europe to diversify its energy sources and routes. Europe has also clearly embraced gas as part of its climate change policy and as an important vehicle to meet the COP21 commitments, and while energy demand is not expected to grow, import demand for gas will increase due to coal-to-gas switching and dwindling domestic gas resources in the North Sea. The IEA projects that the Union will be importing about 70 Bcm of gas by 2020. In this context, the Levantine basin has been perceived as key for our energy security aspirations, but also as a vector for regional stability in a region adjacent to the EU.

Flowing the gas into Europe from the Levantine basin has been a contentious issue with at least three different scenarios competing for policy support and investment backing. The EU has clearly favoured the so-called East Med pipeline, an almost 2,000 km-long pipeline which would connect the Levantine fields with Cyprus to Crete and mainland Greece, and from there, to Italy using the last leg of the Southern Gas Corridor - the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) but also potentially the IGI Poseidon link between Greece and Italy and the projected IGB pipeline to Bulgaria. The pipeline will carry between 8 and 14 Bcm/y. The overall cost of this behemoth project would exceed $5 Billion, with some industry estimates going to over $7 billion. At certain stretches across its route (between Cyprus and Crete), the East Med pipeline will reach depths of up to 2,000 meters which might substantially increase the above cost-estimate. In a recent announcement, Elio Ruggeri, CEO of the IGI Poseidon venture, estimated the costs to reach €11 billion (€6 billion for the Levantine-Greek link, and an additional €5 billion for the section Greece Italy).

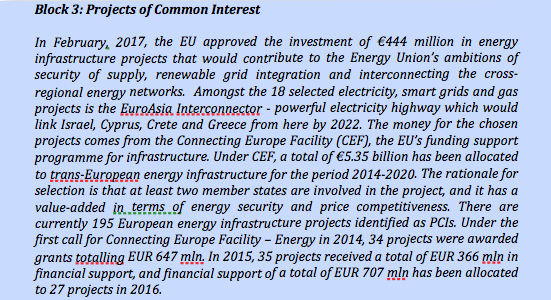

Last year the project has been hastily included in the Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) list and the EU has already committed €2 million (50% of the estimated cost) to the execution of Technical Feasibility Studies, Reconnaissance Marine Survey and Economic, Financial and Competitiveness Studies on the Cyprus-Greece link to inform upstream producers and downstream operators on the project viability and importance for the EU diversification objectives9.

But, despite the EU’s support, forging hundreds of kilometers across complex geological structure, with high seismic activity and in a conflict-ridden region dissuades investment and makes the East Med link a marvelous paper drawing flouting in Commission cabinets but without any private financial prospects. The decline in oil and gas prices have decreased energy companies investment capabilities, which makes private upstream funds even harder to secure. The recent proclamation of Israeli, Cypriot, Italian and Greek energy ministers, trumped by the EU’s very own energy chief on the viability of the project during a largely figurative ceremony in Tel Aviv at the beginning of Aprl is not likely to change the financial appetite of the industry for this project10.

Also, given the volumes and prices of gas transferred, the project might not justify the investment in pure financial terms, but also in more ideological manner, it would not reduce the dependence on Russia per se [EU currently imports about 170 Bcm from Russia, and the East Med pipeline is destined to transport about 12 Bcm]11. Pragmatically speaking, the East Med discoveries represent less than 2% of global reserves, and the availability for exports becomes almost non-existent if we juxtapose the figures against domestic consumption, thus the reserves which might potentially be available for export to Europe might not deliver to intended grand energy liberation plans.

A second project, a pipeline linking Leviathan to Ceyhan in Turkey via Cyprus has also been explored, especially in the context of late diplomatic rapprochement between Israel and Turkey. The pipeline is intended to join TANAP in Turkey and thus flow into Europe from there. The possibility to reach the European market using the Turkey-Greece-Italy interconnector have also been flouted, alongside with a second sleeve reaching Bulgaria via the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria. The region’s challenging geology would make this project extremely difficult to implement and the cost might exceed that projected for the East Med pipeline. The Cypriot question is yet another impediment. The current political situation in Turkey weights on further on the political appetite for this project but also serves as a strong deterrent to industry’s investments. The pipeline might also be perceived as competing with the Russian Turkish stream project, which would hardly be left untackled by the gas behemoth. Russia has already flanked to possibility to fuel Russian gas in TANAP via its TurkStream pipeline thus perpetuating the dependency link with both Turkey and the European Union in an ingenuous spider-web strategy which would eventually cut all potential diversification options for Europe. On European level, the Turkish link might garner less support also due to the escalation of tensions with increasingly authoritarian and erratic Turkish leadership in recent months.

Finally, the Floating Liquified Natural Gas (FLNG) and Floating Condensed Natural Gas (FCNG) are flexible but costly options for the current level of hydrocarbons in the East Med region and projected global commodity prices until 2020.

Deep-dive: Turkey as a key conduit for EU’s diversification plans

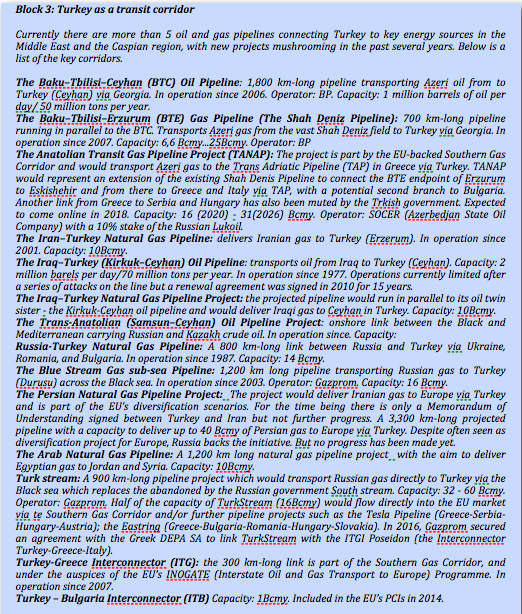

Turkey's annual natural gas consumption in 2016 stood at 48.6 bcm of gas and the country is almost entirely dependent on imports, with Russia being the main gas supplier, providing about 55% of annual consumption12. In the next decade, this consumption would almost double to around 70-75 Bcmy due to soaring refugee population, but also domestic demographics. According to the Turkish Ministry of Energy, Turkey has the second fastest growth of electricity and gas demand in the world after China. Two years ago, the country conducted some exploration activity off the Cypriot coast, which has been promptly interrupted by the Greek Cypriot administration. The conflict on territorial waters is ongoing and if seismic surveys prove further resources around the island, the situation might further deteriorate. The Turkish Energy Minister Berat Albayrak indicated during the CERAWeek in Houston in March, 2017 that the country will renew its exploration activities in the Eastern Mediterranean but also in the Black Sea in the months to come. He also informed that the Ceyhan port is currently being upgraded to become a key energy and shipping hub. This activity has not garnered European attention and could potentially have a dangerous consequences to Europe’s energy calculations. President Erdogan has not hidden his grandiose ambitions to turn Turkey into a key conduit for the distribution of Eastern Mediterranean gas and an indispensable energy anchor and transit zone, thus increasing its geopolitical remit and clout over the EU. The control of the Dardanelle and the Bosphorus straits will bolster his project, and the country has been involved in a complex web of existent or projected pipeline projects over the past few years [see Block 3] with a potentially threatening prospects for the EU, given rhetorical warnings pronounced recently by the increasingly unpredictable Turkish leaders, which might end up in a new, potentially more troublesome dependence than that on Ukraine as a transit.

Turkey is also pursuing a diplomatic rapprochement with Russia. Last October, the two counties signed a deal for the construction of a massive gasoduc (TurkStream) bypassing Ukraine to reach Turkey and from there to fuel gas also in the Southern Gas Corridor - a project meant to reduce EU’s dependence on Russian gas - the counterintuitive logic seems to be lost on the EU decision-makers13. Russia is also building the first Turkish nuclear plant at Akkuyu, thus further engulfing the country into its energy dependence scenario, as it has done with many EU member states as well (the majority of new nuclear plants especially in Eastern Europe are built using Russian technology, by Russian companies and relying on raw materials imported from Russia).

The East Med Geopolitics of Energy: Prospects for the Future

In a world where geopolitics and history did not matter, pulling together regional resources and capitalising on economies of scale in exploration but also export of the hydrocarbon deposits would probably be the most sensible political, commercial, and economic option for the Eastern Mediterranean gas deposits. The exorbitant price tag of a pipeline link to Europe would have been offset by the price reductions expected by a joint exploration. Albeit the scenario’s wide backing by the European Union and the Eastern Mediterranean states themselves, achieving the necessary cooperation has proven fiendishly hard. Strained relationships with contested maritime borders impede the realisation of synergies and the optimisation of gas developments in the region. The jigsaw of political tensions in conjunction with the lack of clear vision and sound energy governance, infrastructure and storage facilities compounds the gas export monetisation trials and tribulations. The reduced upstream budgets of energy majors do not make investments in a conflict-ridden, geologically complex region forthcoming either.

Thus, the anguished debate on the future of the Eastern Mediterranean gas reserves is set to follow its trajectory well into 2017, denting even further investors’ confidence and derailing pragmatic strategies for domestic utilisation and/or regional exports. Or in a surprising gyration, the regional impasse might well herald in the coming year an epiphanic realisation on the limits of grand scenarios for trans-Mediterranean links, and thus, forge a more pragmatic strategising on the domestic and/or regional options going forward. Just possibly. In an interesting development in the end of January, 2017, the leaders of Israel, Cyprus and Greece hinted at the possibility to form a ministerial energy grouping to oversee joint project development. If realised such grouping might well be the harbinger of a wider energy cooperation, either in the framework of the Union for the Mediterranean or via a new regional institutional setting. The three leaders have also expressed interest in the Euro-Asia subsea electric Inteconnector which would integrate the power grids of the three countries and facilitate further political discussions and energy cooperation. But amidst hope and hype, no technical feasibility or economic viability assessments have been undertaken as yet neither for the EastMed pipeline corridor, nor for the subsea Euro-Asia interconnector. The signed preliminary agreement to agree in the future signed in April in presence of Miguel Arias Canete is likely to have a meagre practical follow-up, apart from the familiar stream of summits and accompanying statement. The vision to achieve solid regional energy cooperation seems not to be ready as yet to leave the communiqué drafting rooms, but the hinted ministerial cooperation is a path the region would be well-advised to pursue, and the EU should vehemently support the establishment of a regional institutional setting to facilitate structured dialogue and in time joint project development. This would be the only conduit for the monetisation of the regional gas deposits and for the much vetted regional stability.

Russia

In the coming year, we might also expect Gazprom to intensify its diplomacy in the region and attempt to get a share in the Israeli natural gas industry. This is a key development to follow and with the potential to actually disrupt the regional energy dynamics. Vladimir Putin has already discussed three years ago (in 2014) with Mahmoud Abbas a potential Russian investment in the Gaza offshore gas fields. Rapprochement with Israel might also open the door to Russian involvement in the Leviathan. Once the war in Syria is finished, Russia would have the exclusive rights to drill in Syrian waters which might hide some gas deposits identical to the ones found in Zohr. These projections would compromise any EU diversification blueprints and yet seem not to be even accounted for in any EU East Med scenarios. Russia’s potential involvement in the Southern Gas Corridor attests to the new strategy of the gas behemoth versus the EU and is equally symptomatic of the EU’s myopic vision. The Southern Gas Corridor is meant to transport Azeri gas to Europe via Turkey thus reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas. Nevertheless, the Russian Lukoil has a 10%-stake in the consortium developing the Shah Deniz Pipeline, one the Southern Gas Corridor’s legs. The Russian company has also been granted more than $200 million from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to develop the Shah Deniz gas field. The TurkStream potential entry point into TANAP is also much overlooked in the discussions surrounding the Southern Gas Corridor. Being in denial would not be and have never been a good strategy for the EU. A frank and transparent discussion on the Southern Corridor fuel sources and routes is imperative, for the Union to avoid wasted credibility once again, after Nabucco, and wasted resources in supporting a corridor which might actually never meet its intended diversification objectives fully.

A test of realism

In the months to come, the EU would have to admit that its buoyant proclamations to Cyprus but also Israel on the potential of their gas have been prematurely sanguine. The two countries would need to assess realistically their export prospects also given Egypt’s newly found energy prowess. Israel will implement a fresh gas framework to investors. Rapprochement with Turkey and the development of a direct route between the two countries will indispensably encounter resistance from Nicosia but also, more critically from Moscow. This link is also an option, the EU should be especially vigilant about. Cyprus would either trump in a hinted discovery of a Zohr-like deposit in its territorial waters, or finally abandon the idea of an energy stardom status and enter in serious domestic gasification debate and/or explore pragmatically the potential to use Egypt’s LNG facilities to export the Aphrodite dormant resources. Reaching a unitisation agreement should remain a common goal for both Israel and Cyprus and such development in the months to come might well un-bottleneck important exploration options. Lebanon might also just manage to revamp its restrictive legislation and complete the second first licensing round. Despite a surprising political breakthrough last month with the passing of its first budget in 12 years, ending a record hiatus of public finances, the risk of escalation of tensions with Israel might dent Lebanese ambitions. In Jordan, the government awarded in January two LNG contracts to Swiss Gunvor and Spanish Gas Natural but any potential finding there would feed the domestic market, currently dependent on Qatari LNG.

The above comes to show that a realistic assessment of the potential for the Levantine resources to reach Europe provides a rather sober perspective, much different to the enthusiastic hype which surrounds the flurry of diplomatic activity related to the East Med gas. Thus, hopes and projections of the region to become a European gas mecca might be too sanguine. Marred by regional tensions, industry skepticism, and lack of long-term utilisation prospects, the East Med pipeline would remain a pipe-dream so much as other grand diversification scenarios preceding it. The EU should recognise that referring to the East Med diversification scenario it has once again jettisoned pragmatic engagement in favour of an emotional response. The Union should engage with the issue that bedevil it as an energy hungry continent and rather than compromising its credibility by entertaining yet more improbable diversification scenarios, invest its ingenuity and resources in building large partnerships for the development and furthering of energy efficiency technologies and renewable energy sources, and pursuing a sustainable and resilient low-carbon transition. Promotion of this pathway for the Eastern Mediterranean countries should also be embraced by the Union in our diplomatic activities in the region.

Bemoaning bluntly the incongruity of EU’s diversification scenarios should serve to summon the political will of EU policy-makers to pave the way for a truly independent energy future for the continent which does not interchange one dependency with another and veer towards even more unpredictable partnerships and allegiances. Brussels need to up the ante in its support for a genuine decarbonisation strategy which tackles the energy trilemma with the only viable option: energy efficiency and renewable energy. This would both be feted by supporters and admonished by those the Union try to impress with our grandiose pipe-dreams. And that should be a jolly victory to achieve.